over classrooms

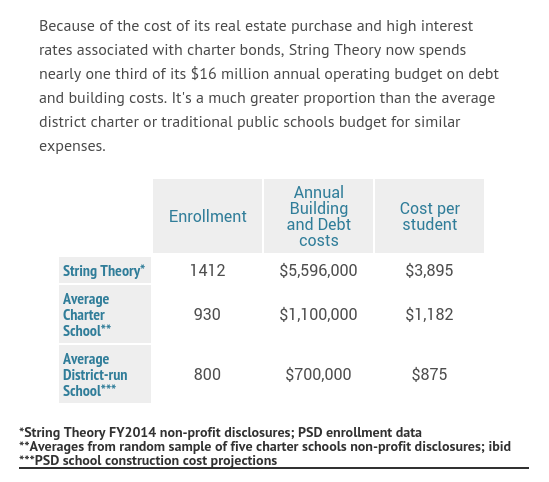

Three Franklin Plaza, a bow-shaped eight-story building at 16th and Vine streets, once hummed with 1,700 GlaxoSmithKline white-collar workers.

Today, it is empty more than three months out of the year, a lone security guard watching over the corporate art still hanging in the lobby.

From September to June, a charter school called String Theory occupies half the floors. The school acquired and renovated this premier office tower in 2013 as part of a $55 million tax-exempt bond deal, arranged with help from the city’s biggest economic development agency.

It was the largest bond deal of its kind in city history.

It is also the most conspicuous example yet of a risky, expensive, and fast-growing financial scheme underpinning the rapid expansion of Philadelphia charters — a market now worth nearly $500 million. But the bond financing behind the mountain of money gets little scrutiny on whether the debt is a smart use of Pennsylvania’s limited educational dollars.

The lack of transparency can translate into deals that may be unsustainable. Shortly after moving into its flashy high rise, String Theory posted its first operating deficit. After revealing they were $500,000 in the red from paying out millions annually to bondholders, administrators told parents they were cutting certain classes and suspending bus service as cost-saving measures.

On the plus side, if the String Theory board members who indirectly own the Center City skyscraper sell it, there could be a big profit. But is this the way charters should operate? String Theory is hardly alone. As the number of privately administered public schools has grown from 55 to 83 over the last decade, more schools have pursued high-stakes bond deals.

Charter schools used to inhabit repurposed supermarkets or old storefronts, but a Philly.com analysis of bond documents showed that an increasing number — one out of three charters today — have bought or constructed newer and larger school buildings with tax-exempt bonds, paying millions in debt and fees to consultants along the way.

Bonds — school debt sold to investors who are gradually paid back with interest — have become popular among charters because they allow lower borrowing costs than standard commercial loans.

Bonds are commonly floated by governments and school districts to get upfront money for infrastructure projects, but charters were long considered too risky an investment because they can be abruptly shut down.

As charter schools became more established, investment prospects improved. But the bonds that charter schools have tapped are still riskier and come with “junk” ratings, carrying high interest rates.

“They’re getting bond ratings that have an eight or eight-and-a-half percent interest rate, whereas a school district getting [government] bonds to finance a project can get much lower interest rates,” said Bruce Baker, a Rutgers education professor.

This leaves charters spending more educational dollars on interest payments — $78 million over 30 years on top of String Theory’s $55 million bond, for instance — at rates that are double or triple what the district pays.

The financing process and real estate transactions themselves also entail millions in consulting and legal fees. Schools like String Theory can become enmeshed in complex and costly deals for marquee buildings that are difficult to sustain.

“There’s no real scrutiny of these deals, and charters end up saddled with big fixed costs,” said Michael Masch, former chief financial officer for the School District of Philadelphia. “They’re saying,‘Look at this really prestigious building we have, that’ll attract people.‘ But it’s a ridiculous amount of money to be spending on the facilities side.”

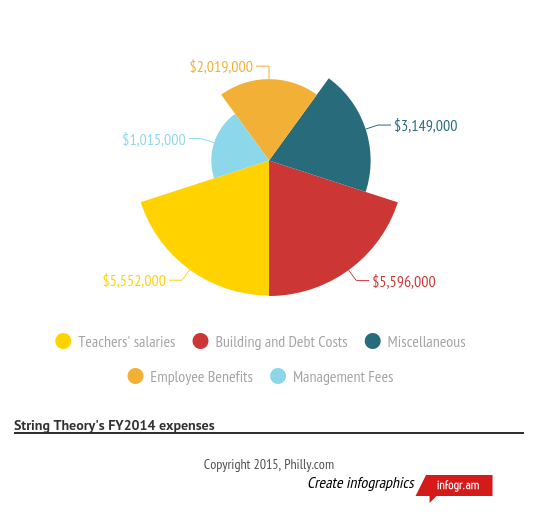

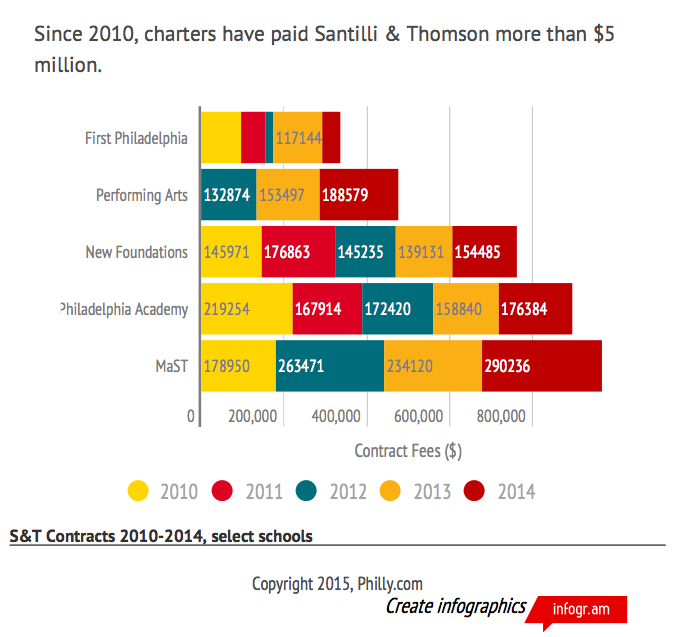

Today, an increasing number of charters are spending more of their budgets paying down debt than on actual instruction. In the case of String Theory, which enrolls 1,400 students, the school now spends nearly one third — $5.5 million — of its $16 million budget just to occupy the half-empty 228,000-square-foot high rise, along with two older, smaller schools in South Philadelphia. That figure is more than String Theory spends on teachers’ wages — $5.3 million.

Put another way, String Theory spends $3,895 per student on its building costs, nearly five times the $800-a-student average the district budgets for debt and building expenses.

The pressure can lead school administrators to push for even more expansion projects — more students means more state funding to pay off debts.

“The current state charter law forces schools into seeking these types of financial arrangements,” said City Controller Alan Butkovitz, who twice since 2009 has released large reports on charter school spending. He noted that efforts to make reforms in Harrisburg have stalled over the last six years.

In financial statements filed in February, the first since the purchase of the GSK building, String Theory reported a $500,000 operating deficit for 2014. But at the same time, school administrators sought permission to open four more String Theory schools, a plan that would more than double the size of its student body.

All four proposals were ultimately rejected by the School Reform Commission. A few months later, String Theory announced it was halting bus service, while cutting French classes and creative writing out of the school’s arts-centered curriculum.

Parents were outraged, particularly those living in South Philly, where the school was first founded.

“I was really very shocked,” said Sue Cook, a Whitman resident who pooled funds with other String Theory parents to arrange for private bus service for their children. “We’ve got to pay this bus company thousands of dollars every month. We have to raise $3,055 just for September.”

Just as String Theory became part of a trend of charter schools pursuing ever-larger bond deals, the school’s fiscal struggles could put it at the forefront of another, more perilous trend that Baker, the Rutgers professor, has observed across the country.

“Nationally, default rates for charter revenue bonds are up,” said Baker, who has researched charter lending patterns. “They’re still pitching [the bonds], saying that the industry remains strong. But default rates are up.”

In December, one of the first district charter schools to receive bond financing, the Walter D. Palmer Leadership Learning Partners Charter, became one of the first to default on its bond debts, shutting its doors abruptly in the middle of the school year.

Today, on Palmer’s Northern Liberties campus, a stray cat has taken up residence beneath the crumbling foundations of an abandoned classroom trailer, next to a gleaming building that was paid for with $11 million in bonds in 2005. Taxpayers have paid out $6 million in debt service, but could end up with little to show for it — the building is on the cusp of being sold to satisfy the remaining debt.

Behind some bond issues is the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp., the city’s largest economic development agency, which has financed such turnarounds as the transformation of the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

The agency has long offered financing to nonprofits, priming industrial expansion and the construction of city museums and universities, with interest from these bonds exempt from federal income tax.

It was the perk of tax exemption that would prove crucial for making risky charter investing more palatable. In 2001, PIDC expanded its role to aid the growing charter segment of the Philadelphia School District.

“It’s not all charter schools,” PIDC president John Grady said. “They have to have a track record — their charter renewed two or three times, having been in business for 10 or 15 years. As the charter school operations market has stabilized, more investors are seeing that as an opportunity.”

The pace of PIDC’s bond authorization has increased sharply in recent years, along with the scale of individual deals. Half of the $468 million in bonds the agency has authorized over 14 years were issued in the last three years.

Critics, like former schools finance chief Masch, took issue with an economic development agency quietly morphing into the de facto charter-financing vehicle in Philadelphia. “PIDC is supposed to provide tax-exempt bonds for economic development,” Masch said. “I don’t see creating charter schools as economic development, in the sense that it’s not bringing new jobs to Philadelphia.”

He described the approval process as opaque at best.

“The School District has a capital budget — it publishes it; people can analyze it. It’s very public and they have to go to City Council every year and answer hours of questions. By decentralizing through charter schools, none of this stuff is really visible until someone decides to write a story,” he said. “Doing it this way also means there’s no public examination to see if charters are keeping costs as low as possible.”

Baker described the system as one that evolved out of necessity, with little foresight. No concrete financing vehicle was ever created for charters, and many schools had in the past relied on leasing buildings or taking out commercial loans with even higher interest rates.

“Who can blame them?” Baker said. “For each of the parties involved, their behaviors kind of make sense. But it’s still stupid public policy.”

To illustrate the failings of this ad hoc system, in which no central authority examines charter schools’ real estate purchases, Baker pointed to redundant transactions that were financed with bonds at great expense to taxpayers.

In 2007, Independence Charter School issued a bond for $18 million dollars with help from the PIDC for the purchase and renovation of the vacated Durham Elementary at 16th and Lombard streets. That school had been built in 1907 and maintained by the district with tax dollars for a century. Now, millions in debt and interest from Independence’s charter bonds are also being paid off with tax dollars.

In situations like these, Baker said, taxpayers are paying for the same buildings twice, while relinquishing public ownership of those properties.

“It’s not that anyone is doing anything ‘wrong,’ ” he said, “But rather that public policy permits a bad deal for the public — one that essentially gives away a public asset while charging transaction fees along the way.”

Masch expressed concern that the boom in charter expansion could reach a point of implosion, as the demand to finance new school buildings is derived mainly by the transfer of students out of traditional district schools.

“There are no new students coming into the Philadelphia school district and yet we’re building all these new schools,” he said. “At some point, you’re going to have to start closing schools.”

Masch also said that because charters get guaranteed funding based on the number of students they enroll, their budgets stayed relatively stable while the district made deep cuts in response to a shortage of state education dollars. As a result, construction of new district school buildings has ground to a halt.

“Whether it’s a plan or a strategy or an unintended consequence, the reality is that you have brand new buildings for charters while district schools are falling apart,” Masch said. “You’re starving one system to fund another.”

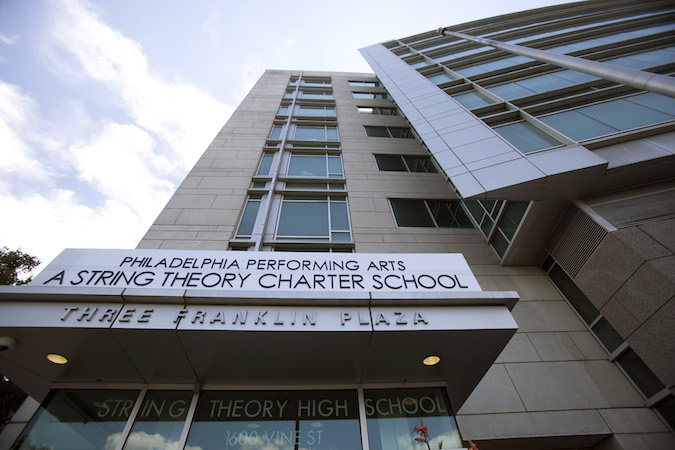

Many of the recent charter bond deals have been helped by Santilli & Thomson, a New Jersey-based firm that has made millions off consulting contracts and bond fees.

The firm, run by ex-Philadelphia School District finance officials Gerald Santilli and Michael Thomson, touts on its website “more than 50 years of combined experience in municipal school management.”

There is no way to know exactly how much Santilli & Thomson has earned in taxpayer-funded contracts from charter schools, according to a district spokesman. The firm did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

However, a Philly.com analysis of financial documents for several charter schools that received municipal bonds found Santilli & Thomson has billed at least $5 million since 2010.

In the case of String Theory charter, the relationship began when founder Angela Corosanite attended a school district meeting in the late 1990s as a ballet teacher interested in starting an after-school program. While there, she recalled in documents from an unrelated court case, she “was approached by a member of the Philadelphia school board” who said she should consider applying to open a charter school instead.

Corosanite didn’t name the school official, but within a year Gerald Santilli was acting as “business manager,” helping set up the first String Theory school, then known as the Philadelphia Performing Arts Charter in South Philadelphia.

After working for 14 years as executive director of fiscal management for the school district, Santilli had moved into charter consulting full-time in 1999, shortly before String Theory was founded, with a group of other ex-district officials, at a nonprofit called Foundations, Inc.

Santilli personally helped found several other schools, like First Philadelphia Charter and its sister school Tacony Academy, before starting his own consulting firm with Thomson.

“After a while, it appears [Santilli] realized that this could be a lucrative and growing business, and that he could make more money doing the work on his own,” said former school district chief finance officer Michael Masch.

Santilli & Thomson was subpoenaed as part of a federal investigation into charter corruption in 2010, but no one there was ever charged with a crime and the firm’s contracts have continued to grow. The charters Santilli helped found have become some of his biggest clients and secured some of the biggest bond deals in city history.

What Santilli does to facilitate these arrangements is unclear. Consultants like Santilli & Thomson face little scrutiny from the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

What is clear is that Santilli & Thomson retains four lobbyists in Harrisburg. And though both partners are registered Republicans in New Jersey, they have together donated more than $12,000 to Pennsylvania Democrats since founding the company.

Santilli & Thomson also works closely with the Center City law firm Sand & Saidel, which specializes in workers’ compensation cases, but provides legal services to a number of charter schools. Partner Daniel Saidel, brother of former City Controller Jonathan Saidel, declined to discuss the nature of his work with charters.

“I’d rather not talk about this because it’s a deeply personal story,” he said. “I don’t like to live in the past.”

Along with the $5 million Santilli & Thomson has billed to charters between 2010 and 2014; Sand & Saidel has billed charter schools at least $1 million, according to financial filings. Each firm also collects a portion of the “cost of issuance” fees attached to bond deals, which can run into the millions. In the case of String Theory, $1.5 million worth of settlement fees were built into the $55 million bond deal, although it’s not clear how the money was split among different consultants.

Most of Santilli and Saidel’s client schools have amassed bond debt while entering into complex lease arrangements that allow them to maximize the amount of money they receive from a state program designed to reimburse charters for a portion of their facilities rental cost.

String Theory’s new skyscraper, the former GlaxoSmithKline building, is actually owned by DeMedici II, a nonprofit controlled by Bensalem-based auto parts manufacturer Javier Kuehnle and South Philly podiatrist Michael Zarro. Kuehnle and Zarro are board members of the school.

String Theory effectively “rents” its building from itself, collecting $188,000 a year through the state’s Charter School Lease Reimbursement Program.

Much of this money is then put toward debt service. The amount of rental reimbursements issued to Philadelphia charter schools has skyrocketed in the last four years, as Santilli’s consulting and the need to pay interest to bondholders has also grown.

Reimbursements rose 79 percent — to $6.8 million annually — while the number of charter schools increased by just 20 percent, state records show. Only a fraction goes to schools that rent their buildings from unrelated owners.

The issue isn’t limited to Philadelphia, according to state Auditor General Eugene DePasquale, who is conducting a statewide review of charter leases.

“About half the charter schools we’ve audited basically have this circular arrangement where there’s an entity that owns the building and an entity that leases the building, and they’re connected,” he said.